Only when the small-scale fishers of Sri Lanka willingly adopt social security mechanisms can their sector be protected and assured of a sustainable future

This article is by Heli De Alwis (heli@cepa.lk), Research Professional, Centre for Poverty Analysis, Sri Lanka

Fisheries play a pivotal role in Sri Lanka’s socio-economic development, providing 50 per cent of the animal protein for the population, contributing to 2.6 per cent of the exports, and securing livelihood opportunities for 6.5 per cent of the country’s employed population. Sri Lankan fisheries can be categorized into marine and inland (freshwater) fisheries. The marine sector can be divided into three sub-categories: offshore, operated by multi-day boats beyond the continental shelf; coastal waters on the relatively narrow, continental shelf in which traditional craft and boats with outboard and inboard engines operate; and lagoon and brackish water fisheries.

Despite the limited number of multi-day vessels, the majority of the Sri Lankan fishing fleet comprises small-scale operators accounting for about 90 per cent of the total fishing fleet of the country and 64 per cent of the total fish production (both marine and inland). The small-scale fishing fleet mainly contains inboard single-day boats (IDAYs), outboard engine fibreglass reinforced boats (OFRPs), motorized traditional boats (MTRBs), non-motorized traditional boats (NTRBs), beach-seine craft and inland fishing craft. The small-scale fishers utilize low technology and little capital, target local markets, remain segregated from other communities, and most often are organized according to caste and ethnicity.

Sri Lanka has no social security scheme for fishers across all sectors, including both marine and inland

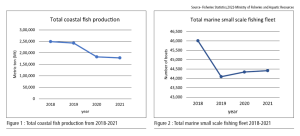

Previous studies conducted on the small-scale fisheries (SSF) in the country reveal that the sub-sector is associated with complex contexts and socio-economic and environmental vulnerabilities, including declining incomes, rising cost of inputs, poor market linkages, climate change and exploitation of natural resources. Moreover, fisheries statistics illustrate that the total small-scale marine fish production and the total small-scale fishing fleet have been declining over the past few years.

Compounding the existing vulnerabilities in the sector, the COVID-19 pandemic, the X Press Pearl container ship disaster, and the economic downturn have made life extremely difficult for Sri Lanka’s small-scale fishers over the last three to four years. COVID-19 had a severe impact on the industry, causing marketing chains to collapse as a result of lockdown regulations. Fisheries livelihoods were further impacted by the ongoing economic crisis—the worst economic downturn after independence—hyper-inflation, a foreign exchange crisis, and high levels of government debt, causing scarcity of fuel and other essential items, frequent power cuts and many other socio-economic repercussions. All commodities, including kerosene and fishing gear, were affected by the skyrocketing inflation of 2022, and small-scale fishing operations were hindered by the lack of kerosene.

Many small-scale fishers are still struggling to recover. They do not have substantial reserves from prior profits; they survive on daily income. For them, handling a crisis becomes extremely difficult. Moreover, the multiple crises have been an eye-opener for the sector, with emphasis shifting to the attention that needs to be paid on strengthening decent work conditions, including robust social security systems, occupational safety, improved living conditions and training.

This article intends to illustrate the current conditions of decent work standards, social security systems, income support systems and training needs within the small-scale fisheries sector. These findings were derived from field research conducted in 2022-2023, including both commercial and small-scale marine fishers in all fisheries districts in the island.

Sri Lanka has no social security scheme for fishers across all sectors, including both marine and inland. Historically, the country had enacted the Fisher’s Pension and Social Security Scheme Act to provide periodic pensions to fishers in their old age, insurance against physical disability, or a gratuity in case of the fisher’s death, through the Agricultural Insurance Board. However, the scheme is currently dysfunctional. No new registrations for pensions are being accepted. Moreover, only a very small proportion of fishers have been enrolled in this scheme, and those who are enrolled complain that the pension they receive per month is woefully inadequate to cover their medical expenses, requiring monthly visits to collect a small amount of money. Faced with such a reality, many elderly fishers who should be retired by now continue fishing, using non-mechanized craft to meet their daily expenses.

The government is currently making efforts to introduce a new contributory social security pension scheme for all fishers, which is more comprehensive and flexible than the old system. Fishers understand the importance of having a social security system and are interested in being part of a contributory pension scheme that provides adequate benefits for them and their dependants. The main concern of the fishers was that a contributory scheme should be designed with a convenient payment system that does not require them spending time travelling or lining up in queues.

However, these pension schemes are solely focused on fishers; others are not covered, whose livelihood depends on fisheries, like onshore workers and fish processors, for example. Fisheries co-operatives and rural fisheries societies have been operating welfare schemes for their members within their own geographical areas for a while now. These schemes include facilitation of financial access for small-scale fishers by providing very low-interest loans, maintaining a fund for disaster relief programmes, distributing stationery to children, and distributing dry rations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, the fisheries societies are not actively operating in all fisheries districts and, therefore, island-wide coverage cannot be expected.

Despite the high risks in the fisheries industry, which is a hazardous source of employment, the majority of fishers are reluctant to engage with an insurance scheme. However, for multi-day fishers, regulations have been imposed whereby they cannot deploy on trips without insurance. But for small-scale fishers, there are no such regulations. Though they accept that their lives are endangered at sea, they are reluctant to obtain life insurance. Lack of trust towards insurance providers, inability to stake claims for injuries, and the long waiting period for receiving claims can be identified as the reasons behind this general reluctance. Given this lack of interest, most small-scale fishers believe that insurance is not essential as they operate within the coastal range. The existing insurance only provides coverage for fishers under the age of 65, while those above 65 are still engaged in small-scale fishing as they are not physically fit enough for multi-day trips.

Despite the high risks in the fisheries industry, which is a hazardous source of employment, the majority of fishers are reluctant to engage with an insurance scheme. However, for multi-day fishers, regulations have been imposed whereby they cannot deploy on trips without insurance. But for small-scale fishers, there are no such regulations. Though they accept that their lives are endangered at sea, they are reluctant to obtain life insurance. Lack of trust towards insurance providers, inability to stake claims for injuries, and the long waiting period for receiving claims can be identified as the reasons behind this general reluctance. Given this lack of interest, most small-scale fishers believe that insurance is not essential as they operate within the coastal range. The existing insurance only provides coverage for fishers under the age of 65, while those above 65 are still engaged in small-scale fishing as they are not physically fit enough for multi-day trips.

Even though fishing is a high risk sector of employment all over the world, occupational safety mechanisms to address the risks involved in the sector are largely lacking. Field research revealed that Sri Lankan fishers operating OFRP boats carry life jackets on board but do not wear them, as they find them disruptive to fishing operations. Many small-scale fishers who operate non-traditional craft do not practise using life jackets at all. As for first aid, while fishers mentioned that they carry first aid boxes with some basic items, most lack knowledge of first aid or the basic actions needed to be taken in a medical emergency. In case of a distress situation, mobile phones are used to communicate with land to ask for help.

Existing practice

Despite small-scale fishers playing a vital role in fulfilling the protein requirements of the nation, policies on developing human resources in small-scale fishing are not adequate. The existing practice is that all fishing techniques are learned on the job. However, the Department of Fisheries conducts training programmes for multi-day boat skippers prior to obtaining their skipper licences. Small-scale fishers revealed during field interviews that they would like to update their knowledge on new technologies in the sector, especially on fishing gear. It was further revealed during discussions that the younger generation is reluctant to enter the sector, preferring off-sea jobs; they do not see fisheries as a profitable business. They prefer work as crew members on multi-day boats, which generates more income than small-scale fishing operations. They also regard the vessel owner as an employer, who is assumed to provide a safety net, especially in a financial emergency.

During our discussions, it was mentioned that small-scale fishers do require proper training and awareness on first aid procedures. Though knowledge of first aid is essential for fishers irrespective of the scale of operation, currently only the skippers of the multi-day boats receive first aid training, even though small-scale fishers have been requesting for such training programmes. They would also like to be trained on multi-day fishing operations so as to help them find employment on multi-day boats.

Proper awareness of savings mechanisms for fisher families, especially for the women, will help them start saving small amounts from their daily incomes

Some fisherwomen say they have received training on post-harvest production from community-based organizations and non-profit organizations. However, most of these programmes were not sustainable, with only a few women succeeding in starting their own small enterprises. They have realized the importance of building up savings and knowledge about offshore employment to maintain a stable income during the off season when fishing is not possible. Their concern was that many fishermen spend their small, daily income on alcohol, leaving no room for savings. Proper awareness of savings mechanisms for fisher families, especially for the women, will help them start saving small amounts from their daily incomes.

The various challenges that small-scale fishers have faced—and continue to face—have made them a vulnerable group, threatening the long-term sustainability of the sector. The issues currently prevalent in the sector motivate the fishers to move out of fisheries and engage in labour in other sectors. Recent fisheries statistics provide evidence of the sector’s declining performance over time. Given that the sector has been operating for decades, fulfilling the nation’s protein requirements, providing a proper social security system, occupational safety mechanisms, access to financial services, and training to enhance their knowledge are the vital steps needed to protect the SSF sector and ensure its sustainability.

There is also an imperative need to create robust awareness among fishers about the importance of contributing to the social security system, participating in insurance schemes, and adhering to occupational safety regulations. Only then will the small-scale fishers of Sri Lanka willingly adopt these social security mechanisms, guided by a better understanding.

For more

Between the sea and the land : Small scale fishers and multiple vulnerabilities in Sri Lanka

https://sljss.sljol.info/articles/10.4038/sljss.v43i1.7641

Coping with the economic crisis -fishing livelihoods and food security. Retrieved from Sunday Observer

https://archives1.sundayobserver.lk/2022/09/11/impact/coping-economic-crisis-fishing-livelihoods-and-food-security-0

Fisheries Statistics. Sri Lanka: Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources

http://www.fisheriesdept.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/FISHERIES-STATISTICS-2020-.pdf

Development of central data base for marine fisheries in Sri Lanka . Department of Fisheries Aqautic Resources Sri Lanka

https://www.grocentre.is/static/gro/publication/212/document/susara09prf.pdf