Women who dominate the shellfish harvest sector in Galicia struggle for due representation and policy inclusion

By Sandra Amezaga (s.amezaga@udc.es), PhD Student, University of A Coruña, Faculty of Sociology, Spain and Secretary, Women Salgadas-Galician Association of Women of the Sea, Spain

On the North-Western region of Galicia in Spain, shore-based shellfish harvesting is carried out mainly by women. With traditional and very simple tools that have remained virtually unchanged over time, women gather in beaches to collect bivalve molluscs, primarily species of clam (japonica, babosa and fina), cockles and razor clams. The strong presence of women in the trade has profound implications, both positive and negative, which determine its main characteristics.

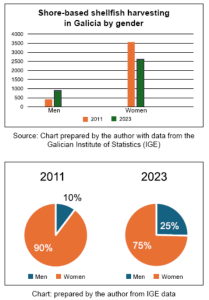

According to the latest official data provided by the Galician regional government there are 3,529 people holding an official license for shore-based shellfish harvesting in the region, of which 2,633 are women and 896 men.

On the Arousa Bay, the main hotspot for shore-based mollusc harvesting, there are 1,544 licence holders, of which 306 are men and 1,238 women.

Even though the total number of shellfish harvesters in Galicia has decreased from 3,970 people in 2011 to 3,529 in 2023, in recent years the number of male licence holders has significantly increased, profoundly changing the male to female ratio. In 2011, women represented 90 percent of all licence holders but in 2023 only 75 percent. Despite the decline, the trade remains predominantly female, in sharp contrast to other fishing activities where women are practically absent, such as fishing, where, according to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Government of Spain, they barely represent 6.15 percent of the total.

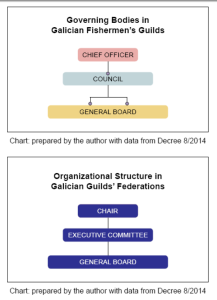

All small-scale fishing activities, such as fishing, and shore-based and vessel-based shellfish gathering (locally known as “on foot” and “on board” harvesting), are grouped together in Cofradías de Pescadores (Fishermen’s Guilds), non-profit legal entities consulted by and collaborating with the Galician administration in matters related to extractive fisheries and fishery management. The Xunta de Galicia (Regional Government) regulates the Guilds. There are currently 63 of these in Galicia, present in all three coastal provinces (Pontevedra, Coruña and Lugo). They all have the following legal governance structure vide Decree (8/2014):

A General Board, which this is the main decision-making and governance body, overseeing all the others, and includes between 10 and 24 members (depending on the Guild’s number of partners) representing all production sectors.

A Council, which oversees general management, administration and government. It consists of the Chief Officer, the Secretary and 6 to 10 members (depending on the number of members of the General Board) A Chief Officer who is the Guild’s representative and Chair of both the Council and the General Board.

The Chair and the members of the Executive Committee are elected from the General Board’s membership.

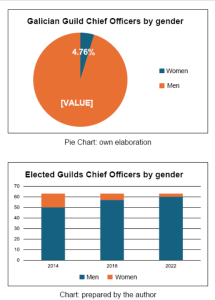

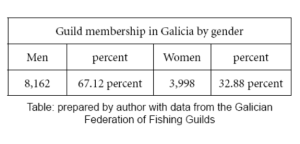

According to data from the Galician Federation of Fishing Guilds, women make up 32.88 percent of all guild members in the region. However, their presence and participation in the governing bodies is far from equal. After the last elections to leadership positions in October 2022, only three guilds have female Chief Officers. These are the Cofradías from Vigo (Vigo bay, Pontevedra Province), Lourizán (Pontevedra bay, Pontevedra Province) and O Grove (Arousa bay, Pontevedra Province). In other words, women make up 32.88 percent of all guild members but are represented in only 4.76 percent of leadership positions in the main small-scale fisheries organisations in Galicia.

According to data from the Galician Federation of Fishing Guilds, women make up 32.88 percent of all guild members in the region. However, their presence and participation in the governing bodies is far from equal. After the last elections to leadership positions in October 2022, only three guilds have female Chief Officers. These are the Cofradías from Vigo (Vigo bay, Pontevedra Province), Lourizán (Pontevedra bay, Pontevedra Province) and O Grove (Arousa bay, Pontevedra Province). In other words, women make up 32.88 percent of all guild members but are represented in only 4.76 percent of leadership positions in the main small-scale fisheries organisations in Galicia.

The sheer inequality between men and women becomes even more worrying when comparing those figures with the results of previous elections held by the guilds. In 2014 a total of 13 women were elected as their associations’ Chief Officers. Four years later, that figure decreased to six until finally in the last elections, in October 2022, only three women were voted to occupy these senior posts.

On upper governance levels, there has never been a woman at the helm in the provincial or regional federations. Clearly, a strategy is needed to reverse this downward trend in terms of women’s participation, not in fishing or shellfish harvesting where they continue to be present in large numbers but in decision-making. The lack of gender parity in fisheries governing bodies exacerbates fisherwomen’s historically precarious work and living conditions.

The traditional gender segregation of fishing activities leads to the acute vulnerability of female-dominated sectors, such as shore-based, “on foot”, shellfish harvesting. Men run the fisheries in Galicia and, despite the economic and social importance of shellfish harvesting in the region, women are outside decision-making spaces where fisheries regulations are negotiated. For example, until last year, different reduction coefficients were used to calculate retirement pensions in shore-based and vessel-based shellfish harvesting.

The Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Fisheries Research, adopted on 17 March 2023, finally aligned the two groups’ reduction coefficient (0.15), while recognising the same entitlement to other trade categories, such as neskatillas – the female relatives of the fishermen, who help unloading, processing and marketing fish; net menders; empacadoras – the fish handlers; and professional divers. These newly included categories, except for professional divers, are made up mostly of women.

The Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Fisheries Research, adopted on 17 March 2023, finally aligned the two groups’ reduction coefficient (0.15), while recognising the same entitlement to other trade categories, such as neskatillas – the female relatives of the fishermen, who help unloading, processing and marketing fish; net menders; empacadoras – the fish handlers; and professional divers. These newly included categories, except for professional divers, are made up mostly of women.

The federations of fishing guilds, represented by their Chairs, have been designated necessary partners by the Regional Government of Galicia to negotiate regulatory frameworks, state aids or labour-related matters. If women are not present at decision-making levels, the issues and challenges they face are neglected by policy. As an example, the annual renewal of licenses in shore-based shellfish harvesting, a female-dominated activity, is conditional on the licence holder’s participation in seaweed removal and surveillance against illegal harvesting. This contrasts with the renewal of licenses for vessel-based licences, a traditionally male-dominated activity.

The federations of fishing guilds, represented by their Chairs, have been designated necessary partners by the Regional Government of Galicia to negotiate regulatory frameworks, state aids or labour-related matters. If women are not present at decision-making levels, the issues and challenges they face are neglected by policy. As an example, the annual renewal of licenses in shore-based shellfish harvesting, a female-dominated activity, is conditional on the licence holder’s participation in seaweed removal and surveillance against illegal harvesting. This contrasts with the renewal of licenses for vessel-based licences, a traditionally male-dominated activity.

“On foot” women shellfish collectors are the only workers in the guilds required to remove seaweed to keep healthy mollusc beds and prevent shellfish mortality. This is hard and unpaid work involving waste disposal techniques for which this category of workers does not necessarily have the proper tools and resources. If this sector was male-dominated or if women shellfish collectors were equitably present on guilds and federations management bodies and involved in social, economic and political dialogue, it is a moot question if the issue would be dealt with in the same way. In my opinion, the answer is not. Women are seen as cheap or free labour, as they have been frequently in the past.

“On foot” women shellfish collectors are the only workers in the guilds required to remove seaweed to keep healthy mollusc beds and prevent shellfish mortality. This is hard and unpaid work involving waste disposal techniques for which this category of workers does not necessarily have the proper tools and resources. If this sector was male-dominated or if women shellfish collectors were equitably present on guilds and federations management bodies and involved in social, economic and political dialogue, it is a moot question if the issue would be dealt with in the same way. In my opinion, the answer is not. Women are seen as cheap or free labour, as they have been frequently in the past.

Shellfish harvesting activities in Galicia underwent a much-lauded professionalization process in the last years of the 20th century, hailed as an example of good planning and governance. The relevance of women being finally admitted as workers in the guilds, the success of their organisational model and, above all, the significance of their inclusion in the Special Social Security System for Sea Workers, granting them social protection benefits, should not be underestimated.

However, 30 years later, it may be time to objectively analyse and assess the progress made from that point to the present day. Recent massive mortality events in the Galician shellfish beds, leading to a complete stop to harvesting in numerous areas, highlight the weaknesses of this type of fishery and the need to reorganise “on foot” activities. A new management system is necessary that can adapt to the current impact of global warming and climate change. Interruption of activity events made it clear that current social protection is not adequate and does not provide coverage to all shellfish harvesters.

Furthermore, low levels of income from shellfish harvesting hinders the necessary generational renewal of a sustainable profession that helps to protect the marine environment and resources.

Equal representation of women in the guilds is a matter of social justice, but it also supports environmental protection and sustainable governance of the Galician coast. The Law 9/1993 on Fishermen’s Guilds in Galicia has become obsolete in this regard, as it favours certain economic groups and penalises women’s participation. No political party in the Galician Parliament seems willing to amend this law; even though women’s associations in the fisheries sector have long called for reform, a proposal that the Guilds and Federations are against. The transformation of shore-based shellfish harvesting and progress towards greater equity and inclusivity necessarily requires a review of current leadership models both in fisheries and in society.

The transformation of shore-based shellfish harvesting and progress towards greater equity and inclusivity necessarily requires a review of current leadership models both in fisheries and in society

As is the case of women workers in other sectors, women shellfish gatherers, are the main caregivers in the household. Many still hold the view that the professional activity of these women is a mere “supplement” to the family economy, a job that provides a little income on the side while they look after their children and other dependent adults and the house. The enormous weight of reproductive jobs drives women further away from full and equal participation in representation and leadership roles.

Public policies theoretically geared towards achieving equality in the sector are often patronising, ineffective and, in many cases, replicate and cement existing stereotypes, treating women as children, unfit for management roles. Gender equality remains a highly sensitive issue in a fishing sector that still resists even minimal changes, such as using a more inclusive name for the guilds (officially known as Fishermen’s guilds) or offering gender-equality training to members and leaders. Lack of transparency also represents a burden when trying to obtain sex-disaggregated statistics and other data elements necessary to better analyse the problems of fisheries from a gender perspective, as required by law.