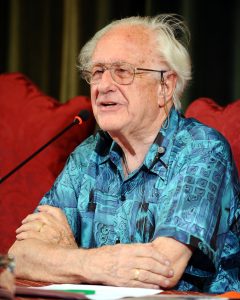

Johan Vincent Galtung (Oct 24, 1930 – Feb 17, 2024)

The scholar of peace and conflict studies will be remembered for critiquing how the industrial model of fisheries was imposed on tropical developing nations

This article is by John Kurien (kurien.john@gmail.com), Former Professor, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, India and Honorary Member, ICSF

Professor Johan Vincent Galtung died on February 17, 2024, in Norway, aged 93. A sociologist renowned for his contributions to peace and conflict studies, Galtung founded the Peace Research Institute of Oslo (PRIO) and Transcend International, two organizations dedicated to promoting peace and non-violent approaches to conflict resolution. Greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, Galtung had doctorates in mathematics and sociology; he authored over 150 books and more than 1,000 articles.

Readers of the SAMUDRA Report might wonder what connected such a profound academic and peace activist with fishworkers and fisheries. The answer lies in 1952, when the UN signed a tripartite agreement on economic development with the governments of Norway and India. Under this was created the Indo-Norwegian Project of Fisheries Community Development (INP) in the southern Indian state of Travancore, which was merged with the new province called Kerala in 1956.

INP was the world’s first development project of its kind. It was inspired by the UN Expanded Programme for Technical Assistance, which was seen as an avenue for post-World War II assistance to the newly independent developing countries. The success of the Marshall Plan in the reconstruction of the war-torn economies of the West was a point of departure for developed economies to extend technical assistance in the form of machinery, aid and expertise to what were called ‘underdeveloped economies’.

Being interested in development, Galtung visited INP areas on several occasions between 1960 and 1969 to hold discussions with the Norwegians and Indians charged with the project. More importantly, he came to meet with the fishing communities who were the intended beneficiaries of the activities of the project.

Galtung was attempting an analysis of INP from the standpoint that it did not achieve its primary goal: raising the standard of living of the poorest fisherfolk in the project region. Several ‘achievements’ of the project–such as the introduction of trawlers or facilitating shrimp export to the US–were certainly not among its original stated goals. These were only unintended consequences of unintended activities, undertaken only for the project’s survival.

Coming from a peace studies framework, Galtung examined INP from the perspective of the underlying structural inequalities and power imbalances it was creating. He also pointed to the depletion of resources and the expanded environmental consequences. Following detailed and systematic inquires and analyses, Galtung wrote an article titled ‘Development from Above and the Blue Revolution: The Indo-Norwegian Project in Kerala’ for PRIOslo, which he had started in 1966.

His views caused an uproar in Norway because INP had been portrayed as a ‘model’ development project. Following this, many more researchers studied INP from various perspectives, examining how well-intentioned development interventions play out in the dynamic reality of local and global socio-economic and political forces.

Galtung visited India again in 1982. This time he made a stop at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) in Trivandrum, Kerala, where Sebastian Mathew (now with ICSF) was pursuing an M.Phil. programme. I was a research associate at CDS but away on a year’s assignment in Hong Kong. Sebastian introduced Galtung to a lengthy socio-economic and ecological analysis of Kerala’s fish economy that I had produced in 1978. Galtung found this to be in line with his own understanding of the evolution of Kerala’s marine fisheries since the 1950s.

Sebastian accompanied Galtung on his visits to the remnants of INP and to the villages where the project was concentrated. He wanted to study for himself the transformations there. After returning to Norway, Galtung was gracious enough to write me a letter of appreciation about my research. A very fruitful collaboration had begun. His framework greatly influenced my subsequent work on INP.

In 1984, when we were planned to organize in Rome the first International Conference of Fishworkers and their Supporters, I invited Galtung to make a presentation on the impact of industrialization in the fisheries sector on its workers. He readily agreed and stayed in Rome for three days.

His presentation was greatly appreciated. Accompanied by George Kent, he detailed impacts fishworkers were actually feeling in their lives. For example, conflicts with trawlers over space and resources; poorly paid and exploitative working conditions on fishing vessels and processing plants; and diversion of fish exclusively for exports, jeopardizing local food security.

A press meet was planned during the conference to impress upon the international media gathered in Rome to cover the FAO/UN World Conference on Fisheries Development and Management. The idea was to have a panel of fishworkers from around the world, supported by some speakers of calibre such as Galtung. He suggested that the panel exclusively comprise fishworkers; his presence was going to merely to assist with translation, as and when needed. And what a presence it was because he spoke eight languages fluently! Following the animated press interaction, Galtung remarked: “This was really a seminar on fishery issues of the highest order!”

In March 1985 I met with Galtung again at Lofoten Islands in northern Norway. It was an international seminar organized by the Norwegian ministry of foreign affairs to evaluate all the fisheries aid projects running with Norwegian assistance. INP was the highlight, naturally—the most discussed and controversial project. Galtung was at his devastating best, giving a detailed exposition of how and why trawlers were introduced into Kerala by the project at a time when they were banned in Norwegian coastal waters, and who in Norway was responsible for it.

Galtung will be remembered primarily for his contribution to peace studies and for his active involvement in mediation and conflict resolution efforts around the world. He facilitated peace processes in numerous conflict zones and has worked tirelessly to promote dialogue, reconciliation and nonviolent resolution of disputes. His work will continue to inspire scholars, practitioners and activists committed to building a more peaceful and just world.

Early critique

The fishery fraternity will remain thankful to him for his early critique of the economic and ecological consequences of imposing the industrial model of fisheries in temperate regions upon many developing nations in the tropics, all under the guise of ‘development assistance’.

For more

Development from Above and the Blue Revolution: The Indo-Norwegian Project in Kerala

https://www.transcend.org/galtung/papers/Development%20From%20Above%20and%20the%20Blue%20Revolution%20-%20The%20Indo-Norwegian%20Project%20in%20Kerala.pdf

Johan Galtung: The Indo-Norwegian Project in Kerala

https://www.transcend.org/galtung/papers/The%20Indo-Norwegian%20Project%20in%20Kerala-A%20Development%20Project%20Revisited.pdf