Small-scale fisheries organizations and other non-State actors could well transform the SSF Summit into a permanent space for global collective action

This article is by Nicole Franz (Nicole.Franz@fao.org), Equitable Livelihoods Team Leader, FAO

The year 2024 marked the 40th anniversary of the first International Conference of Fish Workers and Supporters, held in Rome in 1984 on the initiative of a number of individuals engaged in small-scale fisheries (SSF) around the world. It was convened as a counter-conference to the World Conference on Fisheries Management and Development, organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in which small-scale fisheries actors were not represented. At that time there was no global SSF organizations or social movement.

This counter-conference sparked the foundation of organizations able to fill that gap, namely the International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF), and about a decade later, the World Forum of Fish Harvesters & Fish Workers (WFF) and the World Forum of Fisher Peoples (WFFP).

About another decade later, in 2008, the first Global Conference on Small-scale Fisheries was co-organized in Bangkok by FAO and the government of Thailand. Its theme was ‘Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries: Bringing Together Responsible Fisheries and Social Development’, and it was convened in collaboration with the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC) and the WorldFish Center. It was preceded by a preparatory civil society workshop organized by ICSF, WFFP, the Sustainable Development Foundation of Thailand (SDF), the Southern Fisherfolk Federation of Thailand, and the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC).

A ‘Statement from Civil Society’ delivered at the conference included a “call on the FAO’s Committee on Fisheries (COFI) to include a specific chapter in the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) on small-scale fisheries, recognizing the obligations of States towards them”.

COFI listened. Its deliberations in 2011 launched a participatory process; ICSF, WFFP and WFF joined forces under the umbrella of the IPC Working Group on Fisheries to consolidate views of SSF actors from around the world. The result was the endorsement of the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines) by COFI in 2014, providing the world with a globally negotiated and agreed reference document to support the subsector. Albeit altered in many parts through the negotiation process, the SSF Guidelines reflect specific wording coming from SSF communities.

A ‘Statement from Civil Society’ delivered at the conference included a “call on the FAO’s Committee on Fisheries (COFI) to include a specific chapter in the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) on small-scale fisheries, recognizing the obligations of States towards them”

The first decade

Since their endorsement in 2014, global policy processes and instruments, within fisheries and beyond, have taken up the SSF Guidelines, such as instruments of the Committee on World Food Security, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, and, more recently, the G20 Agriculture Ministers Declaration. Regional policies and initiatives also firmly embrace the SSF Guidelines: the Regional Plan of Action for Small-scale Fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea brokered by the General Commission for the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (GFCM) or the Policy Framework and Reform Strategy for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Africa.

More importantly, National Plans of Action for Small-scale Fisheries now exist in Tanzania, Zanzibar, Uganda, Namibia, Malawi, Madagascar, Senegal and the Philippines. Partners from civil society, the NGO sector and academia, among others, are developing tools or taking action to support the SSF Guidelines uptake and implementation on the ground.

The SSF Summit

Collective efforts of many partners around the world have increased the visibility and consideration of SSF, leading, among other things, to the celebration of 2022 as the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture (IYAFA). In a meeting at the margins of the Ocean Conference in Lisbon in June 2022, FAO proposed to GFCM, the SSF Hub and IPC the organizing of a major convening for small-scale fisheries stakeholders as part of the IYAFA celebrations. No sooner said than done, the first SSF Summit took place in September 2022 in Rome, immediately prior to the COFI session, to create synergies between the two events.

Despite the short time available for preparation, over 100 participants, mostly from SSF organizations, gathered over three days for increased dialogue among fishers and fisher representatives. The result was constructive strategic discussion across SSF organizations, NGOs and others. While much could have been done better, the SSF Summit concluded with a renewed feeling of camaraderie and continued focus for collective implementation of the SSF Guidelines. Importantly, some official COFI delegates joined the SSF Summit, which resulted in the 35th Session of COFI emphasizing “the unique opportunity to gather commitments and recommendations at a Summit on small-scale fisheries, which is encouraged to be held every two years prior to COFI, subject to resourcing, to sustain and inform continued support to the subsector”.

SwedBio joined the somewhat ad hoc organizing committee of the first SSF Summit to not miss the opportunity created by this COFI recommendation. Financial support from the European Commission, matched by contributions from other partners, allowed the holding of the second SSF Summit in July 2024, again prior to COFI. It took place in FAO, symbolically redressing the situation of 1984. This time around, the non-State actors—primarily SSF organizations and social movements—invited government members to attend the SSF Summit in the FAO building.

Reflections: the participants

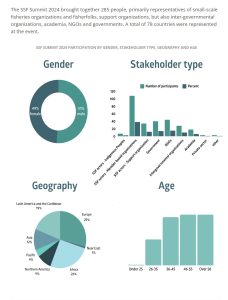

Attended by close to 300 people, representing, in particular, small-scale fishers, fishworkers and their affiliated organizations, the SSF Summit 2024 achieved the objective of providing a platform for engagement. The gender balance was great, but geographical balance needed improvement. Low participation from Asia can reflect a gap in terms of regional organizations, which could help facilitate the flow of information and the identification of participants. The selection process for participants from SSF organizations, social movements and support organizations could be improved, to prioritize those with leadership roles or demonstrated leadership capacities or potential, to support the next generation to constructively drive change and ensure the Summit experience is shared on the ground.

The participation of governments was welcomed and constructive. Brazil, Chile, Tanzania and the US are but some examples of that, as they carried messages about, and from, the SSF Summit into the COFI discussions that followed. NGOs represented another important group of participants; they enabled the participation of many SSF representatives. At the same time, pre-existing tensions between some SSF support groups and NGOs could be felt. The question is whether the Summit could become a space to carve out and address the underlying issues to advance together or however in an overall agreed direction, in line with the SSF Guidelines.

Format and content

Plenary sessions allow all to enjoy the same experience, while break-out sessions allow for drilling deeper, and hearing more voices directly, ideally in a shared language, without interpretation. Arranging for interpretation in many languages is costly, but a pre-condition for inclusion, which is why a lot took place in the plenary. But having regionally organized break-out groups in the Summit was generally perceived as positive, and having the mid-term review of the GFCM Regional Plan of Action for SSF built into the Summit agenda also elevated its importance.

Time is always too short—what was missing was more time for informal discussions and exploration of more innovative and interactive formats, which would also have allowed participants to get to know each other better, a stated objective of the Summit. But new connections developed, leading, for example, to the integration of the Pacific region into the global SSF movements.

In terms of content, sharing experiences about the SSF Guidelines implementation and a focus on two issues—tenure and social development, chapters five and six of the SSF Guidelines—was, in principle, good. In practice, sessions could have benefited from a more systematic preparation, introduction and discussion, to carve out key gaps as well as good practices to inform the way forward. An open question is if a forum of this size can do this, or if the Summit could be better used as a more general, non-technical, accessible space “to collaboratively address governance and development challenges in small-scale fisheries while proposing and sharing solutions to foster and strengthen the implementation of the SSF Guidelines”. This leads to a reflection on the objective of the Summit “to further develop and consolidate the Global Strategic Framework in Support of the Implementation of the SSF Guidelines (SSF-GSF), as a partnership mechanism giving small-scale fishery actors, government representatives and other stakeholders a space to collaborate at a global level”.

Quo vadis?

Implementing the SSF Guidelines takes combined efforts by many actors. These actors—in particular, the non-State actors—need ways to exchange ideas and concerns, and a space for collaboration. For this, IPC proposed the SSF-GSF as a partnership mechanism, giving small-scale fishery actors, government representatives and other stakeholders such an opportunity to collaborate at the global level. The SSF-GSF gives small-scale fishery actors an opportunity to advise others on how they would like to see the SSF Guidelines put into action.

The SSF-GSF, therefore, has an advisory and facilitative role. COFI welcomed the SSF-GSF in 2016. An Advisory Group, consisting primarily of SSF representatives, was established, later complemented by Regional Advisory Groups for Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia and the Pacific, respectively. Additional components of the SSF-GSF are the ‘Friends of the SSF Guidelines’ (governments), as well as a loose group of stakeholders (NGOs, academia, and others) as a Knowledge Sharing Platform (KSP). FAO supports facilitation among these components. A group of ‘Friends’ met a few times, including with the Advisory Group, while the KSP never really materialized.

As COFI has renewed its support to the Summit, it would seem natural to use the momentum to rethink how to operationalize the SSF-GSF; to use the Summit as a regular in-person convening of the SSF-GSF and related partners to review and advance action to implement the SSF Guidelines.

How could this be done? SSF organizations, together with other non-State actors, should drive both the SSF-GSF and the SSF Summit. Rethinking the composition of the SSF-GSF Advisory Group, for example, to ensure regional, gender and age balance and organizational inclusion, and its connection to the SSF Summit organizational committee could be one important step to consolidate a powerful global institutional construct for collective action for SSF.

Piloting the SSF-GSF could be the next important step to explore its potential and impact, for example, in relation to a specific issue or policy process. The Advisory Group could identify and engage with governments as ‘Friends’, inviting them to include views of small-scale fishing communities in their statements and actions. These views could benefit from input provided by the would-be members of the KSP. The Summit could then be the moment to collectively analyse what worked and what did not; how to improve; what to focus on; and how to move forward. It could allow to ground discussions and actions in local realities, but it could also provide ways to make global processes relevant at national and local levels.

All of this would take time, and there would be a lot of learning needed. But, with some patience, the effort could really make a difference for the visibility, voice and impact of SSF representatives in decision-making processes and activities that affect the livelihoods of those that depend on the subsector.

For more

Report of the FAO World Conference on Fisheries Management. Rome, Italy, 27 June – 6 July 1984

https://openknowledge.FAO.org/items/b3a29b46-f832-4f3d-9eb0-09c9d5112b76

Rallying to Rome: Special People. Collective Processes. A Unique Event

https://www.icsf.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/930.ICSF251_ICSF-Rallying-to-Rome.pdf

A global assessment of preferential access areas for small-scale fisheries

http://icsfarchives.net/21288/

Beyond Business as Usual

https://icsf.net/samudra/beyond-business-as-usual/

Small in Scale, Big in Value

https://icsf.net/samudra/small-in-scale-big-in-value/