The Caribbean island nation has done well to provide social security to its small-scale fishing community. It must make them resilient to face the effects of climate change

This article is by Ian S. Horsford (ihorsford@gmail.com), Fisheries and Environmental Consultant, Antigua and Barbuda

Over the past decades the fisheries sector of Antigua and Barbuda has been interwoven into the social, cultural and economic aspects of national development via major improvements in fisheries infrastructure coupled with the modernization of the fleet. Most of the wooden sloops and dories that dominated the sector in the 1970s have been replaced by modern fibreglass launches and pirogues with the latest fishing equipment (like global positioning system and depth sounder).

Fisheries, including aquaculture, is no longer seen as an informal sector outside the purview of national development but as a priceless asset contributing to nutrition, food security, poverty alleviation and livelihood. Additionally, the sector acts as a ‘safety net’ in times of economic crises or when there is a ‘downturn’ in the main engine of growth of the national economy: tourism. This lesson was emphasized during the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent recession, and more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the number of individuals registering and licensing for the first time or renewing their fisher licence increased by 262 per cent in the first half of 2020, compared to the average for pre-pandemic years.

Despite the great strides made with respect to modernization, fishers are struggling to maintain their traditional access and user rights as they compete with the luxury real estate industry and coastal tourism development. Couple this with the catastrophic threats associated with climate change (tropical storms, floods, ocean warming and acidification, beach erosion and sea-level rise, among others) paints a bleak picture for the sector.

According to the Global Climate Risk Index compiled by Germanwatch, Antigua and Barbuda were ranked seventh globally in terms of economic losses from extreme weather based on average percentage losses per unit GDP from 2000 to 2019. This article provides a portrait of social development in the fisheries sector against this backdrop, as well as provide a synopsis of existing policies, legislation, and programmes.

… about half the fishers in Antigua and Barbuda have a robust degree of financial resilience and adaptive capacity

Basic support, social protection

To ensure fisheries policies were consistent with overall social protection policies as well as to support the process of ‘formalizing’ and ‘professionalizing’ the sector, the Fisheries Regulations 2013 were introduced. They state that to be entered into the record as a licensed fisher, an individual is required to be registered under the Social Security Act (1972), and any other labour requirements for Antigua and Barbuda, such as the Medical Benefits Scheme. The enactment of the Social Security Act created a fund to provide the insured population and their dependants with some degree of financial security in the event of sickness, injury, invalidity, maternity, retirement, or death.

An additional condition for fisher registration is engagement with the Fisher Professionalization Programme. Modules are centred around building human capital by providing education and practical skills in areas such as first aid and cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, safety at sea and basic navigation, fisheries laws and protected areas stewardship, small business management and record-keeping, outboard engine maintenance, and seafood safety and quality assurance.

In terms of healthcare, Antigua and Barbuda has a robust system funded through public taxation and levies in support of the Medical Benefits Scheme. The scheme covers primary healthcare including healthcare for specific diseases, as well as refunds for services such as laboratory tests, x-rays, surgery, ultrasounds, electro-cardiographs or similar services, hospitalization, and drugs. Registration with the Scheme is mandatory according to the Fisheries Regulations 2013 and as such, fishers and their families are entitled to all the services within.

With the ‘greying’ of the fishing population, these interventions are becoming increasingly important with respect to retirement, old-age pension and healthcare. In 2002, fishers under 35 years comprised 20 per cent of the population; in 2019, only 15 per cent of sampled fishers were under 35 years. Interventions have also been made into affordable public utilities—potable water, electricity, internet, and telecom—via the Senior Citizens Utility Subsidy Programme. Pensioners, the physically challenged, and those living below the poverty line receive a monthly subsidy of EC $100 (US $37) toward payment of utility bills.

Prioritizing social development has led to the provision of universal free education for children aged five to 16 years, a sharp decline in infant mortality, and an increase in overall life expectancy, with females leading the way according to data from the World Bank (78.0 years versus 75.7 years). Additionally, government has made investments in improving housing stock through programmes such as the EU-funded Housing Support to Barbuda Project, the Low-Income Housing Project, and the Home Advancement (Refurbishment) for the Indigent, as well as new building codes given the islands vulnerability to extreme weather conditions.

Income support measures

The Peoples Benefit Programme is a social scheme that supports people with disabilities and economic vulnerabilities, with a monthly transfer of EC $215 (US $80). This amount is transferred to a debit card to purchase food and personal items in supermarkets and stores selected by the programme. Economic hardship is the typical criterion for qualifying under this programme; for example, households earning less than EC $800 (US $296) per month before payment of bills as well as those with physical disabilities or having children with developmental issues are eligible.

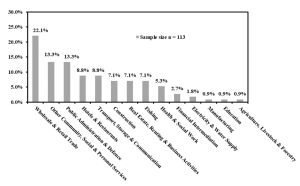

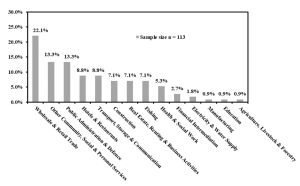

The Board of Guardians, a division of the Ministry of Social Transformation, also provides a fortnightly allowance to the poor and destitute. Notwithstanding these programmes, ‘occupational pluralism’—having more than one job or multiple sources of income from various occupations or enterprises—was a common livelihood strategy or a means of economic security for fishers. In 2019, 51.6 per cent of fishers had another occupation or source of income within fisheries or outside of the fisheries sector. In general, service and sales occupations were the most common complement, including clerical work, taxi or bus driver, bartender, tour guide, and water sport operator.

In terms of migrant fishers, freedom of movement is a right of all nationals of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) in the economic union area

There was also vertical integration of businesses, for example, fishing and water sports or a seafood restaurant. This approach to mitigating business risk in fishing by pursuing economic opportunities in other industries suggest that about half the fishers in Antigua and Barbuda have a robust degree of financial resilience and adaptive capacity. This is supported by the exponential gains in human capital in terms of educational attainment since the late 1990s, with 77.2 per cent of the fishers having a secondary education or higher, thereby enhancing labour mobility and resilience.

Decent work

The Antigua and Barbuda Medium-Term Development Strategy emphasizes ‘decent wages and work conditions’ as vital to sustainable development. The Labour Code establishes the minimum standards employers must meet regarding labour practices and decent work in the country. It includes provisions governing the terms of employment, health and safety issues, the right to join a trade union, collective bargaining, and prohibitions against retaliation towards persons who take industrial action. Article E8 (1) of the Labour Code ensures equal pay for women in both the public and private sectors; “no woman shall merely by reason of her sex be employed under terms of employment less favourable than that employed by male workers in the same occupation and by the same employer”. Article C4 (1) prevents discrimination: “no employer shall discriminate to any person’s hire, tenure, wages, hours, or any other condition of work, by reason of race, colour, creed, sex, age, or political beliefs”.

The code is complemented by specific technical requirements for fisheries such as: minimum age to engage in fishing (16 years); mandatory medical benefits and social security; training in occupational health and safety, and mandatory safety at sea; minimum requirement for food and potable water on board; and a list of mandatory safety equipment for licencing of fishing vessels, including life jackets for each person onboard, flares, VHF radio, tool kit and basic spares for minimum repairs, sound-making device to signal passing vessels, first aid kit and flashlights.

In terms of migrant fishers, freedom of movement is a right of all nationals of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) in the economic union area. These include nationals from Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The Revised Treaty of Basseterre lays out the provisions for individuals to enter and stay indefinitely in any OECS Protocol Member State except in those circumstances where the OECS national poses a security risk for the receiving country.

In terms of healthcare, Antigua and Barbuda has a robust system funded through public taxation and levies in support of the Medical Benefits Scheme

The free movement of persons is linked to broader goals of regional integration and harmonization in Article 13 of the Protocol of Eastern Caribbean Economic Union in the Revised Treaty of Basseterre. The treaty specifies the movement must be without harassment or impediments. Non-OECS nationals intended to engage in local commercial fishing are required to apply for a work permit specifically for the fisheries sector.

Not with standing these gains, work in fisheries is still precarious given that there is inadequate insurance to mitigate the various risks associated with climate change, like hurricanes and floods, and more recently sargassum blooms. In 2017, only 5.9 per cent of vessel owners reported that they had vessel insurance. High premiums, inadequate coverage (like the policy not covering the extent of fishing operations in the maritime limits), and high deductibles were cited as the main reasons for opting for an emergency saving account to cover unplanned expenses. The precarious nature of fisheries has been acknowledged within the regionally endorsed 2018 Protocol on Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management in Fisheries and Aquaculture. However the biggest hurdle to its complete implementation is funding.

One of the most important decisions coming out of the 27th Conference of the Parties (2022), hosted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is an agreement to provide ‘loss and damage’ funding for vulnerable countries hit hard by climate disasters. Caribbean governments are looking to this ground-breaking decision to establish new funding arrangements, as well as a dedicated fund, to assist Small Island Developing States in responding to loss and damage. This along with disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation, taking a whole-of-society approach, ensures that the most vulnerable in society are included.

According to the United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction, “poverty is both a driver and consequence of disasters, and the processes that further disaster risk-related poverty are permeated with inequality.” To overcome these challenges, the most vulnerable must have a seat at the negotiation table; they include female-headed households, youth, and fishing communities in low-lying areas. Initiatives such a Mainstreaming Gender in Caribbean Fisheries can empower and up-scale the participation of women and youths in the governance and stewardship of fisheries, thereby unlocking society’s full potential—the old adage ‘a rising tide lifts all boats.’

For more

Social Development and Sustainable Fisheries: Antigua and Barbuda

https://icsf.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/930.ICSF227_Social_Development_Antigua_Barbuda.pdf

Antigua and Barbuda: Springing Back into Shape

https://icsf.net/samudra/antigua-and-barbuda-social-development-springing-back-into-shape/