Women in small-scale fishing communities bear the worst impacts as coastal space in the Indian Ocean region is increasingly encroached upon by state and private activities

Gayathri Lokuge (gayathri@cepa.lk) Centre for Poverty Analysis (Sri Lanka), Amalendu Jyotishi (amalendu.jyotishi@apu.edu.in) Azim Premji University (India), Holly M. Hapke (drhollyhapke@gmail.com) University of California, Irvine (USA), Ramachandra Bhatta (rcbhat@gmail.com) Snehakunja Trust (India), Karin Fernando (karin@ cepa.lk) Centre for Poverty Analysis (Sri Lanka), Derek Johnson (Derek.Johnson@umanitoba.ca), University of Manitoba (Canada), Nicholas Karani (nickarani78@gmail.com) Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (Kenya), Kyoko Kusakabe (kyokok@ait.ac.th) Asian Institute of Technology, Ajit Menon (ajit@mids.ac.in), Madras Institute of Developments Studies (India), Betty Nyonje (bnyonje@hotmail.com) Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (Kenya), Francis Okalo (francisokalo@yahoo.co.uk) Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (Kenya), Sereyvath Prak (praksereyvath@cird.org.kh), Cambodian Institute for Research and Rural Development, Joeri Scholtens (J.Scholtens@uva.nl) University of Amsterdam (Netherlands), Nadiya Azmy (nadiya_a@cepa.lk) Centre for Poverty Analysis (Sri Lanka), Nuwanthika Dharmaratne (nuwanthikawrites@gmail.com) Centre for Poverty Analysis (Sri Lanka), Channaka Jayasinghe Centre for Poverty Analysis (Sri Lanka), Prasanna Surathkal (pras.kota@gmail.com) Azim Premji University (India), Prabhakar Jayaprakash (prabhakarjp@gmail.com), Tata Institute of Social Sciences (India) and Bhagath Singh A. (bhagath.red@gmail.com) French Institute of Pondicherry (India)

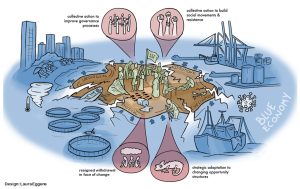

This article is based on a cross-regional study that focused on how ruptures in the form of environmental stress and political economic pressures impacted small-scale fishing communities and were especially mediated by the intersectional social relations of gender, ethnicity/race, caste, class, and place. Drawing upon the work of David Harvey, the research team investigated how capitalist accumulation physically, discursively, and institutionally constrained access by small-scale coastal actors to spaces for action. Our observation is that the space for action by small-scale actors and populations in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is increasingly being encroached upon by state and private activities. We label these processes of dispossession as ‘shrinking space’.

We have taken a materialist feminist approach in our analysis to capture the gendered ruptures and adaptations to the phenomenon of shrinking space. This approach allows us to investigate the four dimensions that affect the material conditions of women and men’s lives. These are economic and environmental factors, political-legal-institutional (governance) relations, social structures, and cultural norms/ideologies and practices. We have applied this framework of analysis to five case study locations: Kenya, India- west coast, India- east coast, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia.

The case of Kenya shows how the construction of factories (fish processing, steel making, cement, and seaweed storage and processing) has adversely affected the livelihoods of women seaweed farmers. These developments have not only reduced their income but also led to loss of working space and land for burial and shrines. The women seaweed farmers have collectively protested these developments and have sought stakeholder engagement and compensation.

In the state of Karnataka on the west coast of India, small-scale fishers are affected by commercial private port construction, tourism development, and coastal aquaculture expansion. Also, they are now in competition with the fishmeal industry for fish resources. Added to this, coastal erosion has displaced small-scale fishers, especially women who process fish. Small-scale fishers have been evicted from the use of accreted land for livelihoods and income with the loss of space to dry their fish or to dock their boats. They also face access restrictions due to tourism development. Small-scale fishers have collectively fought against port construction. Women who are reliant on land for fish drying and marketing activities are particularly affected. Employment created by port and road construction has benefited men more than women.

In the state of Karnataka on the west coast of India, small-scale fishers are affected by commercial private port construction, tourism development, and coastal aquaculture expansion. Also, they are now in competition with the fishmeal industry for fish resources. Added to this, coastal erosion has displaced small-scale fishers, especially women who process fish. Small-scale fishers have been evicted from the use of accreted land for livelihoods and income with the loss of space to dry their fish or to dock their boats. They also face access restrictions due to tourism development. Small-scale fishers have collectively fought against port construction. Women who are reliant on land for fish drying and marketing activities are particularly affected. Employment created by port and road construction has benefited men more than women.

In Tamil Nadu on the east coast of India, spaces once available to small-scale fishers have shrunk due to aquaculture expansion. Aquaculture has also increased ground water salinity with adverse impacts on drinking water supply. Being primarily responsible for domestic water collection, women are acutely affected. In the transition from marine capture fishing to aquaculture, a shift in fisheries work from fishing to non-fishing caste groups is also observable.

In Sri Lanka, small-scale fishers, suffering the impacts of an ongoing socio-economic crisis, are affected by a reduction in fish catch and in fuel supplies for fishing. Large-scale development projects such as the Port City and environmental disasters such as the X-Press Pearl ship oil spill add to their woes. Women are worst affected since they are not recognized as fishers, and therefore excluded from any compensation drives. However, women fish sellers reliant on supplies from traditional, non-mechanised boats have been less affected, despite the fact that they face the threat of growing numbers of men from external communities entering fish trade. Women, with their proximity to traditional market spaces, have acted collectively to secure market spaces and livelihoods.

In Cambodia, tourism development has usurped coastal land. Women fishers are worst affected since they fish near shore while men use boats to fish in the deep seas. However, men too are affected by reductions in catch. Women have had to diversify their livelihood to supplement the diminishing household income. The collective struggles of the small-scale fishing communities were weakened by internal divisions and a growing sense of disempowerment, despite which, however, women are still resisting the tide.

Across the five case study sites, we see Blue Economy Growth initiatives generating both ecological and social-economic ruptures in the form of environmental degradation, economic dispossession, and marginalization. These exacerbate other climate-related effects, all of which disproportionately impact women fishers. A common impact across the region is ‘shrinking space’ for small-scale fisheries and displacements in ways that are gendered. However, the specific form of these impacts varies as do local responses to them.

These variations bring out how Blue Economy policies, their impacts, and the space for adaptation is geographically contingent. An intersectional materialist feminist approach and attention to gender reveals both diversity in place and diversity across places; this yields a more nuanced understanding of how Blue Economy development is impacting small-scale fishers across the Indian Ocean.